Interstellar Breakdown, Hidden Details & Theories | MOC

Interstellar is a visual masterpiece that is not only based on scientific reality but also presents a storyline that touches upon deep human emotions.

Additionally, director Christopher Nolan has made the cosmic narrative of this 2014 film paradoxical, giving the audience a chance to understand the film in their own way. This is why, even after watching Interstellar multiple times, you always notice something new and intriguing.

Hi Superfans, I’m Swapnil, and this is a complete breakdown of Interstellar, featuring hidden details and easter eggs.

To commemorate the 10th anniversary of Interstellar, the film has been re-released, and in this article, I will:

#1 Simplify the movie’s story so much that even a 10-year-old can understand it.

#2 Answer all your questions and technical details that you might have overlooked while watching the film.

#3 Highlight the most interesting hidden details and easter eggs because I know you always look forward to these!

#4 Point out some unanswered questions from this almost perfect script because mistakes deserve attention too.

#5 Discuss three intriguing theories about the ending of Interstellar because what’s the fun of watching such a movie without exploring theories!

And finally, #6 – my goal while writing this article is to enjoy this masterpiece thoroughly myself.

So, without wasting any more time, here’s a spoiler warning, and let’s begin our journey into Interstellar!

#1 Interstellar Story Explained

The story of Interstellar is set around the year 2067.

The movie’s protagonist, Cooper, is a former astronaut who has now become a farmer. He lives with his family on a dying planet Earth, which is suffering from a devastating blight that has ravaged its surface and atmosphere. The blight has wiped out almost all food crops, leaving only corn as the last viable crop. However, corn too will soon be depleted, which means that Earth will no longer be habitable.

Time is running out, and NASA launches a mission to save humanity. The feasibility of this mission hinges on just one thing—a wormhole that has appeared in space, which scientists believe has been positioned there by future humans.

These future humans are far more advanced than us and possess higher-dimensional knowledge, scientific skills, and evolutionary abilities that allow them to manipulate space and time.

This wormhole serves as a gateway beyond our Milky Way galaxy, functioning like a tunnel to distant galaxies. NASA has sent out several manned probes, or space shuttles, to search for a new planet, a new home that could be habitable like Earth. Out of these, three probes send back positive signals to Earth.

As Cooper investigates some unexplained occurrences in his daughter Murph’s room, he follows these clues to NASA’s headquarters, where he learns all the details of the mission.

Despite his daughter’s protests, Cooper is sent with a team to NASA to explore the locations of these probes and determine which planets are suitable for human habitation, ultimately aiming to choose a new world where humanity can relocate after leaving Earth.

BUT does everything go according to plan?

In their first visit, the planet turns out to be uninhabitable, and due to its proximity to a massive black hole named Gargantua, gravity affects time in a significant way.

According to Einstein’s theory of relativity, the closer you are to a massive source of gravity, like the black hole Gargantua, the slower time moves for you.

However, for those millions of miles away on Earth, or even in their space station located a bit farther from Gargantua, time will continue to advance normally. This means that when they return to their space station, while only a few minutes may have passed for Cooper, 23 years have gone by on Earth.

By this time, his daughter Murph has grown up, and she makes a surprising discovery—she needs to solve a complex mathematical physics problem related to gravity to send humans to the space station.

And the answer can only be found from one place—the center of a black hole. Figuring this out is currently impossible for humanity.

On the second planet in space, Cooper and his team discover that the scientist Dr. Mann had reported false data to save himself from danger.

He tries to deceive them, resulting in an accident that kills one crew member. Then, in a second accident, Dr. Mann dies, and their main spaceship gets damaged. Because of this, they have no fuel left to return to Earth, and their last option is to move forward in the hope that the third planet will be habitable. However, due to the low fuel supply, they devise a risky plan—using a slingshot maneuver around Gargantua’s gravity to gain a speed boost.

This risky plan will work, but the mission can only be successful if Cooper and the robot Tars manually detach two spacecraft when their fuel runs out, allowing the main mothership to continue its trajectory toward Edmunds’ planet.

This means Cooper will have to sacrifice himself to Gargantua’s gravity, which would make it nearly impossible for him to return.

Cooper makes the ultimate sacrifice, hoping that if he and his robot, TARS, can somehow retrieve the crucial data—the gravity equation—from inside the black hole and send it back to Earth, they can save humanity.

Their slingshot maneuver is successful, and Cooper and TARS plunge into the black hole. As they await what should be their demise due to the black hole’s gravity, something unexpected happens—they find themselves inside a Tesseract.

Theoretically, Cooper should have been killed inside the black hole, but it’s implied that the Tesseract structure around him was created by future humans specifically to help him. This is why the black hole cannot destroy him. We don’t fully understand the mechanics of the Tesseract, as it’s not something that can be easily explained.

This Tesseract resembles a library, where a bookshelf unfolds across multiple dimensions. Cooper realizes that this is the same bookshelf from his daughter Murph’s room, but here, multiple timelines exist simultaneously. He can see both himself and Murph at different moments and positions, suggesting the existence of a multiverse—a concept we’ll discuss further later.

Inside the Tesseract, because gravity can control time, Cooper is able to access different moments from the past.

Cooper realizes that he can communicate with Murph in both the past and present. Using gravitational fields, he knocks books off her bookshelf and moves the hands of the clock he gave her before embarking on the mission.

Through this new gravitational communication method, Cooper transmits the crucial data from inside the black hole to Murph, which she needs to solve the equation that will allow NASA to transform a large spaceship into a mode of transport to evacuate the remaining humans on Earth into space.

As soon as Cooper accomplishes this task, the Tesseract structure propels him out of the black hole—straight into space.

Drifting in space, he comes into the radar of the space station that was launched from Earth, thanks to his equations. It is there that he is rescued.

Now, according to Earth’s timeline, Cooper has lived for over 100 years, but he looks just as young as he did when he started the mission. This is due to the theory of relativity I mentioned earlier.

On the space station, he meets his daughter Murph, who has aged significantly and is now on her deathbed. Here, he learns that humanity is preparing to shift to a new planet and is traveling there on the spaceship based on his formula.

In the end, Cooper returns to space to help Dr. Amelia Brand, who is going to the third and final planet—one that is indeed habitable. Unbeknownst to him, the rest of humanity has already survived, and she is trying to re-colonize this new planet on her own. Cooper heads toward her so he can deliver the good news about the survival of humanity on Earth.

This is where the movie concludes.

And now comes the most interesting part!

#2 Multiple Questions, Technical Details & Ending Explained

1. Wormhole Anomaly

At the beginning of the film, when Cooper learns that the US government is funding a secret NASA project to find a new planet similar to Earth for humanity, he questions how NASA can accomplish this in such a short time—because we know that it takes decades just to reach the nearest galaxy.

In reply, Professor Brand explains that there has been an anomaly.

The term “anomaly” means “something unusual”: it refers to something that is different from the norm, basically something that doesn’t fit into the expected pattern.

It can be positive or negative: While it is often used in a negative context, an anomaly can sometimes be positive depending on the situation.

- Example situations:

- A person who is significantly taller than all their family members.

Here, he explains that they believe an unknown civilization—which he refers to as “They”—has placed a wormhole near the planet Saturn, which will act like a shortcut in space.

His fellow space traveler, Romilly, uses the example of a paper with a hole to explain how a wormhole works. – video

So, a wormhole acts like a bridge that connects two distant points by using the fourth dimension.

Moreover, there is another anomaly in this movie that I’ll discuss next.

2. “They” in Interstellar Explained

In the movie, all the characters initially believe that “They” refers to an advanced alien or supernatural species. It seems as though they have provided humanity with the wormhole and binary messages to save them, as they cannot directly communicate with humans. Dr. Brand theorizes that these beings are 5th-dimensional, perceiving the 3D world in a completely different way.

However, in the final act of Interstellar, it is revealed that what NASA thought was an alien race is actually two separate but connected entities:

- The first is future humans who can manipulate space-time.

- The second is Cooper, who communicates with his daughter Murph inside the Tesseract.

This means that the unexplained phenomena that NASA attributed to aliens were actually caused by Cooper’s actions in the future. When Cooper sacrifices himself for Plan B, he reaches a Tesseract inside the black hole that was specifically created for him by future humans.

These future humans knew how their past unfolded and how they managed to escape from Earth. That’s why it was those future humans who placed the wormhole near Saturn in the past and created the Tesseract.

Since Cooper and Murph are the saviors of humanity, the future 5th-dimensional humans specifically create the Tesseract for Cooper, so he can communicate with Murph in the past and relay the data collected by TARS. The Tesseract acts as a filter, showing 5D information in a 3D format (which is set up in Murph’s room).

As is typical in every time-travel movie, people will debate if future humans created the Tesseract, then who created it for them so they could survive into the future?

Because if the Tesseract didn’t exist in the first place, they wouldn’t have survived at all.

This is what the paradox is.

The answer to this question is left up to the audience by Christopher Nolan.

3. Bootstrap Paradox

Virodhaabhaas means paradox in Hindi.

A “paradox” is a statement that seems to contradict itself, but upon careful consideration, it might actually be true or hold a deeper meaning.

Ek “paradox” aisi cheez hai jo khud se hi contradict karti hai, lekin jab aap is par gehra sochne lagte hain, toh yeh sach mein ho sakti hai ya ismein koi gehri soch chhupi hoti hai.

For example, saying that something is both “hot” and “cold” at the same time seems impossible at first glance; however, it forces you to think a bit deeper to grasp the real idea behind it.

Here are a few examples of different types of paradoxes:

- Grandfather Paradox

- Barber Paradox

- Logical Paradoxes

- Bootstrap Paradox

- Fermi Paradox

- Achilles and the Tortoise Paradox

- Liar Paradox

- Fletcher’s Paradox

In “Interstellar,” the paradox depicted is the “bootstrap paradox,” where a character sends information back through time, creating a loop in which the necessary information to initiate an action actually comes from a future event.

To clarify with an example from the movie: Cooper transmits data from inside a black hole to his past self, helping him solve the equation necessary for saving humanity. BUT the information he is sending is the very solution he is trying to find.

This creates a paradox and establishes a closed loop where cause and effect are interconnected.

Similarly: This Movie’s Second Paradox Related to Future Humans

If “they” are the future generations of current humans, and Cooper saves humanity, then how can “they” exist in the future if Cooper hasn’t saved humanity yet?

A well-known example of this paradox is from The Terminator movie series: In the first movie of this series, John Connor sends Kyle Reese back in time to save Sarah Connor, who is John Connor’s mother. The paradox arises later when it is revealed that Kyle Reese is actually John Connor’s father. By sending Kyle Reese back in time to save his mother, John Connor essentially creates himself in the future.

Another example of a bootstrap time paradox is the chicken-and-egg dilemma, where a chicken sends its egg back in time, and that same egg is what the chicken eventually hatches from.

Interstellar presents this “bootstrap paradox,” but it also offers an alternative explanation that helps solve this paradox, which I will discuss at the end.

4 Time Dilation Explained

This movie is based on the ideas of theoretical physicist Kip Thorne, who believes that while we view the universe in 3D, there may actually be at least 5 dimensions in total. According to some theories, forces like gravity can leak between dimensions.

In Christopher Nolan’s films, time is often a crucial theme, but in Interstellar, this concept is depicted at its most extreme level.

The best example of time dilation is seen during the visit to Miller’s Planet.

Since this planet is located near a massive black hole (Gargantua), its gravitational pull slows down time. This means that 1 hour on Miller’s planet equals 7 years on Earth!

Amelia explains that due to the effects of gravity on time, the Endurance team got trapped on Miller’s planet — VIDEO.

The beacon signals they thought had been active for years were actually signals sent just a few minutes earlier—meaning that Dr. Miller must have sent the beacon signal as soon as he landed after seeing the water, and shortly after, he was killed by a huge wave. But due to time dilation, this signal appeared to arrive on Earth over several years.

Cooper wants to complete the mission quickly because he knows that if they stay there for even a few hours, several years will pass for his family back on Earth.

But unfortunately, that’s exactly what happens.

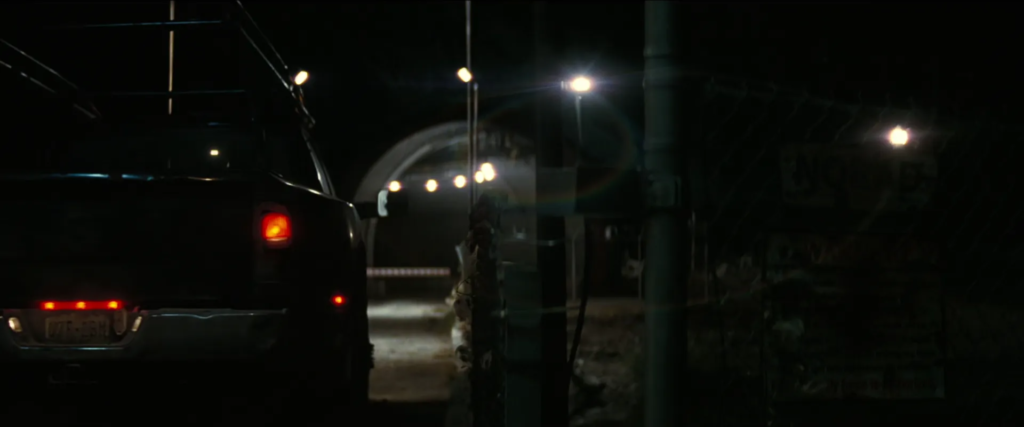

When Amelia and Cooper return to the Endurance, they discover that 23 years have passed for Romilly while Cooper and the team have experienced only about 3 hours!

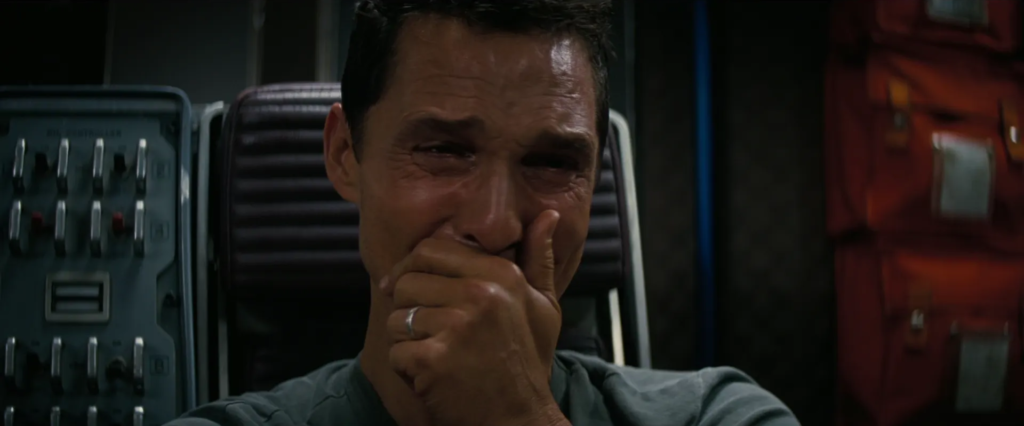

This is why when Cooper watches video messages from his family on Earth, he is shocked to see that Tom and Murph have grown up and their lives have changed significantly.

If the gravity had such a strong effect on Miller’s planet, just imagine how extreme it would be at the center of the Tesseract singularity.

Cooper is shown taking time to eject from the Tesseract, but for humanity in general, it represents a duration of half a century, meaning 50+ years.

Thanks to relativity, Cooper survives and eventually reunites with Murph—who is now over 100 years old.

Murph realizes that there’s no longer any reason for Cooper to remain there. Her son Tom has passed away, and Murph won’t be around much longer herself. VIDEO

No parent should have to watch their child die. My kids are here for me now. Go.

And rightly so, she sends him away.

5 The Plan

If the Endurance team manages to find a habitable planet, Dr. Brand has proposed two plans for the survival of humanity:

- Plan A: While the Endurance team is in space, Dr. Brand will attempt to solve an advanced equation that would allow humans to control fifth-dimensional physics, especially gravity. If he succeeds, NASA plans to launch their existing working lab as a huge space station capable of taking the remaining people from Earth into space.

- Plan B: If Dr. Brand fails in his research, NASA has already stored fertilized human embryos from various DNA sources on the Endurance space station. In case Earth is completely destroyed, these embryos will be used to restart humanity. In this scenario, the Endurance team will settle on a habitable planet and raise these embryos to create future generations.

BUT it is later revealed that Professor Brand was never actually working on Plan A. He had already attempted the advanced equation, which was only possible if data could be obtained from a black hole—something he believed was totally impossible.

He was using the ruse of Plan A to encourage Earth’s leaders to come together and build the necessary infrastructure, which was secretly crucial for the success of Plan B. Dr. Brand believed that people wouldn’t work solely to save humanity; they also needed hope for their personal survival.

And that hope was created by his fabricated Plan A.

6 Are Both Plan A and Plan B Successful?

When Cooper and Amelia learn through Murph’s video message that Plan A was actually a lie, they decide to pursue Plan B — shifting their focus to the third (and final) planetary option, which is Scientist Edmonds’ planet.

However, Cooper doesn’t entirely dismiss Plan A as impossible. He utilizes the Endurance spacecraft and the Gargantua black hole to perform a slingshot maneuver, intentionally sending TARS into the black hole, hoping that TARS can transmit valuable gravitational data back to NASA to assist in solving Professor Brand’s equation.

Additionally, Cooper sacrifices himself by detaching from the Endurance to reduce the spacecraft’s weight, allowing Amelia to safely reach Edmonds’ planet.

This means that even if TARS fails, Amelia will still be able to implement Plan B, ensuring that humanity can survive in the future.

But of course, Cooper’s journey leads to a different ending — ultimately, both plans come together: Plan A focuses on solving the gravitational equation to save people on Earth using large spaceships, while Plan B ensures a fresh start for humanity by finding a new habitable planet.

7 What is Tesseract in Interstellar & Its Use of Time and Space

The effect of gravity on spacetime is what allows Cooper to communicate with Murph inside the Tesseract.

This isn’t the same Tesseract from the Marvel Universe that holds the powers of the space stone.

In our universe—yes, in this real universe—a tesseract is a geometric term that describes a 4-dimensional cube. Just as a square can be represented as a cube in 3-D space, a tesseract is the 4-dimensional equivalent of a cube. (Here, the fourth dimension refers to time.)

The film shows that within the Tesseract, gravity can bleed into different dimensions. This is how Cooper is able to knock books off Murph’s bookshelf to create a message (“S-T-A-Y”). Similarly, he spreads dust on the floor to send the map coordinates of a location—using binary language—which helps his past self learn NASA’s location.

Most importantly, this 5th-dimensional gravity communication allows Cooper to manipulate the hands of Murph’s watch, embedding TARS’ collected data into the watch’s ticks using Morse code.

Later, when Murph translates this coded data, she receives all the information needed to give humanity a deeper understanding of space and time. This is why by the end of the movie, Plan A becomes possible, allowing the remaining humans to escape from Earth.

8 Why Didn’t THEY Provide a Direct Solution – So Many Twists?

One question that arises is why these ‘they’—the future humans—provide such twisted information. Why go through the trouble of creating a wormhole, sending people to another galaxy, and then placing the Tesseract between black holes? If they could just send the gravity equation in an email, there would have been no need for all this effort.

The simple answer is the communication barrier.

Future humans likely don’t know exactly what we need. They may be so advanced that they no longer possess physical bodies. Because of this, they struggle to understand what we require and how to convey that information to us. However, they did know that we needed some information from the black hole, and they understood that Cooper could extract this information. It’s possible they had knowledge of his past as an astronaut and his love for his daughter, Murph.

To make it easier to understand, think of it like communication between a human and an ant.

A human—like you—can observe a stream of water approaching an ant colony, which will drown them, and you want to save them.

From your point of view, you can see that the ants are in danger from the water. But you have no way to communicate with them.

In other words, you can’t just speak or write to convey your message to the ants.

This is what a communication barrier is.

Your communication method with the ants is so fundamentally different that there’s no common ground between you.

The ants know they are getting wet, but they don’t have the information that if they climb onto a nearby rock, they will be safe.

However, if you guide one ant using a stick towards a hill, it can see that the top is dry. Then, that ant could go back and communicate with the rest of the colony, helping them understand how to save themselves.

This is similar to what the future humans did; they didn’t help directly but provided indirect guidance to past humans so they could find their own way to rescue themselves. I really hope this explanation made sense and that my editing wasn’t in vain!

9 How Did Cooper Meet Murph?

At the end, Cooper’s survival and meeting with Murph is entirely based on the theory of time.

If we consider time as a straight line that only moves forward, then the entire story doesn’t make sense. The plot of Interstellar is only possible if time is not linear, but instead operates like a loop or a Mobius strip.

Yes, similar to the Mobius strip discovery in Avengers: Endgame, where time travel became possible due to Tony Stark’s insights.

However, in Interstellar, this concept is portrayed in a more practical and realistic manner.

In this narrative, time bends and curves, which is why Cooper is able to influence events from before his present timeline. This bending of time allows for connections and interventions that would be impossible in a strictly linear timeline. This interaction makes the emotional climax of Cooper and Murph’s reunion not just feasible but deeply profound within the framework of the story.

10 The Meaning of Interstellar

Finally, what is the meaning of Interstellar?

If something happens or is located in between stars, it’s termed interstellar. When you dream of interstellar travel, you envision soaring through the vastness of space — perhaps encountering some extraterrestrial beings along the way.

Prof. Brand’s Recurring Quote Captures the Essence of the Film

Interstellar is a story that embodies the human spirit of exploring the unknown.

The film’s ending and Cooper’s return to space reinforce the message that Professor Brand echoes repeatedly through a poem:

“Do not go gentle into that good night,

old age should burn and rage at close of day.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

The movie illustrates that humanity is at its best when individuals are fearless and ready to venture into the unknown — whether it’s through scientific discovery or the pursuit of love.

In the end, Cooper embodies this spirit; he embarks on a new journey without any guarantees. This act symbolizes the relentless pursuit of understanding and connection, reflecting a core message of the film: embracing curiosity and daring to explore the uncharted territories of existence.

#3 Hidden details & Easter eggs

1) Murph’s First Dialogue has 3 Callbacks

In Interstellar, every dialogue has a purpose, as everything comes full circle by the end of the movie. The center point of the entire story is Murph’s childhood bedroom—the very place where a “ghost” plays with gravity and knocks books off her shelf.

At the film’s beginning, there’s a small scene where Cooper wakes up from a nightmare, and Murph, standing next to him, says:

“I thought you were the ghost.”

This seems like a random childhood conversation, but by the end of the film, it proves to be true.

Yes, it was Cooper who was sending messages by messing with Murph’s bookshelves.

Then, during another conversation when Cooper is about to leave Earth, he says:

“When you become a parent, you become a ghost of your children’s future.”

He elaborates that children remember things their parents have said and done, and in their memories, parents become ghosts to their kids. Murph lives this throughout her life, cherishing the memories of her father, but this relationship is not shown in a straightforward manner.

Moreover, this concept is also metaphorically validated.

In the finale, when Cooper arrives at Murph’s deathbed, he has become that very ghost Murph had predicted—an eternal father figure, still young, while his daughter has aged significantly.

Isn’t this the essence of the ghost concept? According to mythology, when someone becomes a ghost after death, their age stays fixed at the time of passing.

What appeared to be a casual remark actually served as a powerful foreshadowing—illustrating how time and distance transform Cooper into a ghost in Murph’s life. This complex interplay of time, memory, and love reflects the essence of Interstellar and highlights the emotional depth of their relationship.

2) Natural vs. Unnatural

Continuing with the ghost aspect — Murph’s belief that there is a “ghost” in her room is something she holds onto, regardless of her brother’s teasing.

In Interstellar, gravity and love are two significant themes, and both are fundamentally invisible. Similarly, another major theme in the film is the concept of ghosts — again, things that are unseen.

Ghosts are considered supernatural beings, and believing in them within a scientific narrative appears unnatural since science does not validate such phenomena. Yet, love, too, cannot be scientifically proven, and yet we trust in it. As Amelia Brand beautifully puts it, “Maybe we just need to believe in something even if we can’t understand it.”

This statement resonates on a philosophical level, highlighting the intersection of belief and understanding. It suggests that while empirical evidence is critical in the scientific realm, there are realms of human experience — like love, hope, and even the concept of a ghost — that transcend pure logic and invite us to embrace a level of faith.

This philosophical inquiry into the intricacies of human emotions, existence, and our connections with one another makes a powerful statement in Interstellar. We’ll circle back to this idea as we delve deeper into how these themes intertwine and ultimately drive the narrative forward.

3) Murphy’s Law – Good or Bad?

In the film, Murphy’s Law is initially portrayed as a negative concept:

“Anything that can go wrong will go wrong.”

This seems to suggest that if something bad can happen, it will eventually occur. However, it is possible that this is merely one perspective.

Perhaps it is relative, like Einstein’s theory of relativity—what appears to be bad could, from another angle, actually be good.

At the start of the film, when Murph, Cooper, and Tom are on their way to town, their truck gets a flat tire. In frustration, Tom exclaims that it’s due to Murphy’s Law, and Murph feels disheartened.

But then, a drone flies overhead, and they immediately chase after it.

If they hadn’t had their flat tire, they might not have stopped at that exact moment and would have missed seeing the drone altogether. In this case, what initially seemed bad actually led them to a new discovery.

This suggests that Murphy’s Law is not just about bad luck; it can also be a gateway to new opportunities.

I believe this aligns with the film’s overarching theme. The end of Earth, which at first appears catastrophic, prompts humanity to take the actions necessary for their future advancement. So, when something unfortunate occurs, it invites us to try and look for the silver lining.

This philosophical reflection encourages us to remain open-minded and adaptable, recognizing that challenges can often lead to unforeseen opportunities and growth. The narrative of Interstellar profoundly illustrates this idea, underscoring the resilience of the human spirit in the face of adversity.

4) You never find out Cooper’s first name

Interstellar mein Matthew McConaughey ke character ko Cooper naam se bulaya jata hai. Initially lagta hai ki ye unka first name hi hai.

Asal mein, hume kabhi bhi Cooper ka first name pata hi nahi chalta. Wo apne surname se itna jud jaata hain ki climax me jab space station ka naam “Cooper Space Station” sunta hai toh sochta hai ki wo uske naam par rakha gaya hai, jabki ye uski beti, Murphy Cooper, ke naam par hai.

Of course uska naam Cooper Cooper nahi ho sakta.

Apparently Wiki and script ke hisab se Joseph Cooper hai, jo puri movie me use hota hi nahi.

5) There Is No Wildlife

Ye ek chhoti si detail hai jo aapse aasani se miss ho jayegi, lekin ye Interstellar ke theme ko aur meaningful bana deti hai. & that is movie me ek bhi animal ka na dikhna.

Cooper ki farm pe na gaaye/bhains hain, na murgiyan, na kutte-billiyon jaise pets.

Na toh aasman me birds udte dikhte hain, na hi background me insects ka sound hain.

Ye chhoti si detail Earth ke destruction ko silently highlight karta hai. Ye sirf ek agriculture crisis nahi, balki ek extinction-level event hai. Christopher Nolan ne wildlife ko deliberately exclude kiya taaki bina kisi dialogue ke audience ko Earth ki condition samajh aaye.

6) The Strange Ticking Sound on Miller’s Planet

In Interstellar, the crew’s visit to Miller’s planet presents a unique experience due in large part to the gravitational effects of the nearby black hole, Gargantua. As a result, time on Miller’s planet runs significantly slower compared to Earth. The mission feels particularly stressful, especially because an eerie ticking sound begins to play in the background as soon as they arrive on the planet.

This ticking sound is not just a random noise; it occurs at a precise interval of 1.25 seconds. According to the calculations, each tick corresponds to a passage of one entire day on Earth.

The crew spends 3 hours on Miller’s planet, which, when translated into Earth time, equates to a staggering amount. If we calculate this based on Earth time:

- 3 hours on Miller’s planet translates to 60 seconds / 1.25 seconds = 48 ticks for 3 hours.

- Thus, 48 ticks (1 tick = 1 Earth day) means they experience the equivalent of 48 days on Earth.

- 48 days using the conversion of 365 days in a year results in approximately 0.13 years—but this is just for the time they spend on the planet.

However, if we consider the overall impact of time dilation due to the proximity of Gargantua, spending just 3 hours on Miller’s planet corresponds to nearly 29.5 Earth years.

This is illustrated through two different interpretations of the time spent:

- Using the exact time dilation factor: 48* 60 * 3 = 8640 seconds, equating to 8640 / 365 = 23.6 years on Earth.

- Or calculating how many Earth days have passed according to the planet’s ticking: 48 ticks * 1.25 seconds means that while they spent a brief period on the planet, years have flown by on Earth.

Moreover, this ticking sound hints at a deeper narrative detail regarding Dr. Miller, the original research scientist for whom the planet is named. Given the time dilation effect, it suggests that she must have arrived on that planet not long before the crew, approximately 1 hour and 15 minutes prior to their arrival, even though Earth had been receiving signals from her for almost 10 years. This discrepancy illustrates the significant consequences of time dilation, reinforcing the film’s themes of relativity and the subjective nature of time.

By incorporating such carefully thought-out details, Christopher Nolan enhances the film’s scientific foundation and emotional resonance, creating a more profound viewing experience that highlights the complexities of time, space, and human connection.

7) References to 2001: A Space Odyssey

Christopher Nolan drew considerable inspiration from 2001: A Space Odyssey, embedding several references and visual callbacks within Interstellar. Here are some notable examples:

Example #1: The design of the A.I. robots, TARS and CASE in Interstellar, closely mirrors that of HAL 9000, the iconic supercomputer from 2001. Both feature a distinctive visual element with their red camera “eyes,” which evokes a sense of both intelligence and eeriness.

Example #2: The rectangular shape of the robots in Interstellar serves as a nod to the iconic monolith from 2001. This shape, representing advanced technology and ideas, hints at a connection between human evolution and discovery in space.

Example #3: The representation of the black hole and the Tesseract in Interstellar showcases mind-bending geometry and abstract shapes similar to the climactic ending of 2001. Both films explore reality-distorting dimensions, challenging the viewer’s perception of time and space.

8) You Can Tell Dr. Brand Is Lying About Plan A & B

In Interstellar, Dr. Brand, played by Anne Hathaway, convinces Cooper to join the Endurance mission, promising a chance for humanity to leave Earth. However, as the film progresses toward its third act, it becomes apparent that her “Plan A,” which involves relocating humanity to a new planet, was never genuinely anticipated to succeed.

The formula necessary to facilitate Plan A’s success requires data obtained directly from inside a black hole’s singularity—something that is practically impossible for human beings to achieve. This means that the arguments Dr. Brand uses to persuade Cooper to join the mission are fundamentally misleading.

Several scenes vividly display Dr. Brand’s attempts to dodge difficult questions, revealing her uncertainty and the deceptive nature of her motivations. This foreshadowing adds layers of tension and drama, as viewers gradually see the cracks in her facade.

9) Mann’s Survival Instincts

Dr. Mann, portrayed by Matt Damon, serves not just as a traditional villain but as a complex antagonist driven by his fear and survival instincts. His character adds depth to the narrative, juxtaposing the film’s themes of human connection with the darker aspects of self-preservation.

Interstellar fundamentally narrates a story about human connections, yet it initially presents the mission as one devoid of emotional ties. The crew sent through the wormhole was meant to operate independently, without attachments, in pursuit of the “greater good.” However, this assumption proves flawed; Mann illustrates how fear can lead to isolation and moral compromise.

He conceals the true conditions of his planet to save himself, acting out of fear rather than altruism. His behavior underscores the idea that genuine human connections are crucial for survival—not just because they motivate but because they enable trust and collaboration in desperate circumstances.

Ultimately, the film challenges the notion that detachment is the pathway to success, positing that it is the bonds we forge and the love we share that give us strength in the face of adversity. This paradox reflects the complexities of the human experience, emphasizing that our deepest connections are what truly sustain us.

10) Over 80 Years for a Quick Hello

When Cooper attempts to console his daughter before embarking on his perilous journey, he discusses the concept of time relativity with her, which offers a poignant perspective on the potential consequences of space travel. This dialogue rings exceptionally true upon the film’s resolution—Cooper’s age difference compared to his daughter turns out to be much greater than he anticipated.

By the end of the film, Cooper reunites with Murph, but only during her final moments. The inhabitants of the space station inform him that he is now 124 years old on Earth. This staggering revelation means that he had been absent from his daughter’s life for over 80 years. After their heartfelt embrace, he effectively re-establishes a connection with her after almost a lifetime apart.

Despite the bittersweet nature of this reunion, there is solace in knowing that he is granted this precious moment, however fleeting, to be with his daughter.

11) Gravity

The theme of gravity serves as a powerful visual and narrative device throughout Interstellar. From the very beginning of the film, we observe dust particles drifting in a way that creatively illustrates the concept of gravity in action.

In the movie’s concluding scenes, we witness a baseball game played as a simple yet profound demonstration of gravity’s significance in everyday life.

Miller’s planet, with its formidable tidal waves, starkly represents the physical aspects of gravity, showcasing the immense forces it exerts in extreme conditions. Furthermore, the in-space rotations of the Endurance spacecraft to create artificial gravity exemplify the film’s exploration of different gravitational phenomena.

Lastly, the black hole Gargantua stands out as the most potent gravitational object depicted, embodying the deepest mysteries of space-time.

Gravity, in the film, symbolizes an invisible force that draws objects toward one another, prompting a deeper reflection on human emotions, particularly love.

“Pyaar wahi cheez hai jo time aur space ko surpass kar sakti hai.”

— Miss Brand

The narrative suggests that love, much like gravity, possesses the power to transcend time and space. Throughout the mission, Cooper feels an unyielding gravitational pull back toward his children, particularly toward Murph.

Their eventual reunion is portrayed as a culmination of this connection, where love acts as a force that ultimately brings them back together, mirroring the effects of gravity. This beautifully intertwines the themes of science and emotion, presenting love as the ultimate binding force in the universe, capable of bridging vast distances across both time and space.

12) Sentiment vs. Science

Dr. Mann’s assertion that “our survival instinct is our greatest source of inspiration” raises an essential question about the driving forces behind human actions. But is this always the case?

Cooper himself embarks on the mission primarily to save his children, demonstrating that his profound love for them serves as his primary motivation. Likewise, Amelia Brand is on the mission with the intent to reach Dr. Edmunds, the object of her affections. This scenario introduces a compelling dichotomy: Lovers vs. Realists—sentiment versus science.

Lovers are those who believe in the power of love and emotions, represented by characters like Cooper, Amelia Brand, and Murph. In contrast, Realists trust in science and pragmatic approaches, exemplified by figures like Dr. Brand, Dr. Mann, and Tom.

These two groups represent distinct ideologies:

- Realists take a more practical stance, focusing on scientific methodologies and calculations.

- Lovers are driven by emotions, intuition, and love’s transformative power.

Dr. Mann’s characterization by Amelia Brand as “the best” is a revealing moment, yet it ultimately proves to be misleading.

Initially, world leaders believed that the crew of the space mission should have no emotional attachments. The rationale was that, without emotional connections, the crew could make decisions that prioritize the mission and the survival of the human race more easily.

Ironically, it is the humanity and emotional bonds within the Endurance Team that empower them to accomplish their mission successfully.

For instance, on Miller’s Planet, Doyle chooses to save Amelia Brand instead of focusing solely on his own survival. Romilly, rather than leaving the crew behind, waits in solitude for 23 years inside the Endurance for his comrades to return. Cooper sacrifices himself by entering the black hole, all for the sake of saving humanity. Lastly, Amelia Brand, despite losing her entire crew, valiantly sets off alone toward Edmonds’ planet as the last hope for humanity.

What drives all these characters to perform such monumental acts? It’s their deep human emotions and connections—purely for love.

This exploration of sentiment versus science underscores the film’s central argument: human connections and emotions are not just peripheral to survival; they are essential to it. As Interstellar illustrates, love and emotional ties can motivate actions with far-reaching implications, providing strength and resilience in the face of insurmountable odds. Ultimately, it is the interplay of both sentiment and science that shapes the human experience and our capacity to overcome challenges.

13) Love Solves The Gravity Equation

Continuing with the theme of love, we delve deeper into the question that defines our humanity: What makes us human? What is it that allows us to experience emotions and empathize with others, rather than merely reacting to our primal instincts, like survival?

Dr. Mann suggests that before one faces death, they often reflect on the faces of their loved ones, confirming this notion when Cooper finds himself on the brink of death. Yet, Amelia Brand poses a thought-provoking question: “Why do we love those who are gone? What is the social utility of this?”

The truth is, love resists scientific explanation. It is this very love—a father’s love for his daughter—that ultimately enables Cooper and Murph to crack the gravity equation.

When Cooper dives into the black hole as a final attempt to save Murph, it’s a testament to the depths of his love for her. His actions are driven by an unwavering belief in his bond with Murph, embodying the idea that love transcends even the most daunting challenges.

Murph, in turn, manages to find the solution through the signals Cooper sends because she trusts that her father would never abandon her. This trusting intuition, rooted in their father-daughter love, leads her to believe that he will always find a way back to her, not because of logical reasoning, but because of the emotional connection they share.

It is this love that serves as the missing ingredient in solving the gravity equation. The equation itself—while grounded in scientific theory—becomes inseparable from the emotional ties that underlie the human experience.

Thus, in this scientifically robust narrative, the true essence of solving the gravity equation is revealed to stem from love. The film beautifully illustrates that while science can explain many phenomena, it is love that truly binds us, drives us, and ultimately illuminates the path to our salvation. Love, in this context, becomes the force that overcomes the limits of time, space, and even the harsh realities of our universe.

#4 Unanswered questions

1) What is the Cause of the Blight in Interstellar?

At the beginning of Interstellar, Earth’s crops have been largely destroyed due to a global blight that has wiped out all forms of plant life. Corn is the only viable crop left for humanity, but it, too, will eventually run out, leaving people with no source of food.

However, the film doesn’t delve into the specifics of this blight — whether it’s bacterial, fungal, or something extraterrestrial. We don’t know if it evolved naturally or if human actions created it. The origins and reasons behind the blight are left unanswered.

2) Cooper’s Luck is Astronomically Unbelievable

In Interstellar, Cooper’s luck is pushed to the extreme. While it’s true that his survival largely depends on his piloting skills, a significant part of it also comes down to sheer probabilities.

When he jumps into Gargantua, many laws of physics are broken. As he falls into the vortex, the debris from his ship makes us question how he manages to survive as a human being in such dire circumstances.

Not only that, but Cooper also travels back through a wormhole without a spaceship and encounters humans near Saturn.

If we can accept the idea of a wormhole anomaly, we might as well consider all these other extraordinary events as well!

3) How did Murphy know about Brand?

Space jitna vast hai, ye kisi bhi human ke liye ek highly improbable situation hai ki is pure space me wo exactly wahin dikhta hai jahan spaceship & humans use notice kar paye. Cooper ki survival mein uski skills se jyada uska luck & risk taking abilities ka role tha.

4) They relayed complex quantum data via morse code

Cooper tesseract ke through jab Murphy ke bedroom mein bookshelf ke peeche trapped hota hai, tab yahin se wo gravity ko manipulate karke, Morse code ke zariye data ko usiki di hui watch me feed karta hai.

Although Interstellar mein kafi cheejen scientifically true li gayi hain, & yes i’m not a maths expert, but ye specific point, ki morse ke through itna complex quantum data itne easily transmit kiya ja sakta hai, hajam nahi hua.

Climax scene me jab finally Cooper Murphy se uske death bed pe milta hai, toh wo kehti hai ki kisi bhi parent ko apne bachche ko marte hue dekhna nahi chahiye, isliye wo Cooper ko aage badhne ke liye motivate karti hai – Video “Brand. Wo wahan hai. Camp set up kar rahi hai. Akeli… ek ajeeb galaxy mein,”

Lekin wo kaise jaanti hai ki Brand ab bhi zinda hai?

Ye ek plot hole hai jo ek single line ke saath asaani se fix kiya ja sakta tha agar wo log sirf ye mention karte ki unhe uska message mila – ya signal mila.

Interstellar ki kahani 80 se zyada Earth years, ek wormhole, ek black hole, aur anek light-years ko cover karti hai… but ye chota sa confirmation audience ke upar hi chod diya gya hai.

#5 Weird theories

1) Cooper Was Dead The Whole Time

Cooper never survived the crash shown in the opening dream sequence.

Theories suggesting that “X character was dead the whole time” can often be quite dull, but in the case of this film, this theory feels surprisingly fitting.

A significant part of the film is its opening sequence, where Cooper wakes up from a dream about a flight crash. This dream establishes Cooper’s character but is never addressed again, raising the question of whether it serves a greater purpose in the story. Themes of death frequently arise in Interstellar, and Dr. Mann also reflects on how a parent looks into the faces of their children when facing death.

With this idea in mind, it wouldn’t be entirely wrong to suggest that Interstellar’s narrative consists of the final glimpses before Cooper’s death, where he imagines a reality where he gets a random chance to go on a space voyage and save humanity, thus saving his children as well. Additional clues, such as the name of the Lazarus space expedition and Murph calling Cooper her “ghost,” hint at thematic undertones of the afterlife. The emotional core of Interstellar lies in the relationship between Cooper and Murph, and Cooper’s ultimate desire for a mind-bending space odyssey that brings him back to his daughter makes complete sense.

2) The Planets Were Never The Intended Destination

It never mattered to “them” where humanity settled.

In Interstellar, Cooper and his crew set out to assess the potential for human settlement on three planets as part of the Lazarus expedition. To reach these planets, they enter a black hole near Saturn. There are various theories about the purpose of this black hole, and the film hints that it was created by “them,” meaning future five-dimensional humans, to assist humanity’s survival. One Redditor has observed that “they” never intended for humanity to reach these planets; rather, they used the black hole to find a solution to Dr. Brand’s gravity problem.

This is an intriguing theory because it contradicts Dr. Brand’s belief that the planets and the eggs represent the end-game solution, rather than focusing on saving what remains of humanity on Earth. By placing Cooper in charge of the mission, Brand inadvertently selects the right person, as Cooper’s adventurous and intuitive nature allows him to reach the Tesseract and help transmit the solution to the equation back to Murph. For the five-dimensional beings in Interstellar, it does not matter how humanity survives; what matters is that humanity continues to exist in some form and progresses toward becoming “them.”

3) Christopher Nolan’s Films Are Connected

A theory connects Interstellar to Tenet and Inception.

In today’s media landscape, where everything seems to exist within a shared universe, it’s not surprising that audiences are exploring connections between Nolan’s works. One theory proposed by Twitter user FILMDILFS links Interstellar to Inception and Tenet, all of which explore different aspects of dystopian societies and sci-fi concepts. The primary connection in this theory is between Interstellar and Tenet, suggesting that Interstellar takes place in the future and that the Time Bomb was created to prevent Earth from reaching its barren, uninhabitable state.

Auteur filmmakers have successfully linked their films in various ways. Clues within Quentin Tarantino’s movies hint at a shared Tarantino universe as they frequently reference one another. Both Lars von Trier and Edgar Wright have trilogies that share only thematic connections rather than an overarching narrative. It may be a stretch to claim that Nolan ever planned to overlap his stories in his solo films, but entertaining that idea is still intriguing.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Interstellar stands out as a remarkable cinematic achievement that blends breathtaking visuals with profound themes of love, sacrifice, and the human spirit’s resilience. Christopher Nolan’s unique storytelling invites viewers to explore its complexities and paradoxes, ensuring that each viewing feels fresh and enlightening. As we celebrate the 10th anniversary of this iconic film, it’s the perfect time to revisit its multifaceted narrative and the rich layers of meaning woven throughout.

Whether you’re a newcomer trying to wrap your head around the intricacies of time travel, or a seasoned fan eager to uncover hidden details and theories, there’s always something new to discover. Through this article, I hope to enhance your appreciation for this masterpiece and guide you through its captivating universe. So, as we embark on this exploration of Interstellar, let’s dive deep into its nuances, challenge our understanding, and, most importantly, savor the extraordinary journey that Nolan has crafted.